How Reciprocity with Nature is Integral to Our Survival

Why it is important to include Indigenous perspectives for problem solving and maintaining timeless wisdom of living in harmony with the natural world

We continue from last week when Wildlands featured an eight year study to close monumental gaps related to mineral rights, risk framework, risk assessment and science. Indigenous references and first-hand knowledge were utilized to promote, include and expand voices with Western science perspectives. Jo Ellen Hinck, of the United States Geological Society (USGS), partnered with Carletta Tilousi, Havasupai Tribe, to publish their paper and present their work. Ms. Tilousi is busy representing the Havasupai and All of life. Last week and this week’s essays are summaries of the study and interview with Ms. Hinck. Today’s essay focuses on Indigenous perspectives, specifically the Havasupai, as shared in their study. The same poll is included in both essays.

Please share your comments and take an opinion poll at the end of this essay.

Uranium is used for energy, electricity, space exploration, medical, industrial, military and defense all over the world.

Should uranium mining near the Grand Canyon be banned to protect and honor the Indigenous, the Havasupai Tribe’s health, well-being, governance and connection with nature?

Do you think we should mine near the water that serves millions of people?

Is a peaceful agreement that honors and serves All life possible?

Ask your friends to take the poll. Results will be shared with USGS, the Havasupai, EPA and U.S. Forest Service.

Havasuw baja—People of the Blue Green Water

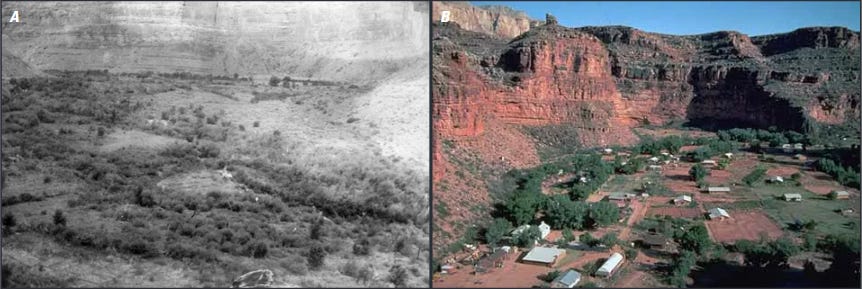

The Havasupai population is 755 Tribal members (as of July 2023), and is one of the smallest federally recognized Tribes in North America. Their reservation consists of 74,867 hectares of the Grand Canyon, which was made by congressional action of the Grand Canyon National Park Enlargement Act of 1975 (Public Law 93–620, 88 Stat. 2089). Havasupai, or Havasuw baja, means People of the Blue Green Water honoring travertine-rich water that forms several distinctive waterfalls and Havasu Creek. Historically, many Pai Tribes inhabited the land around the Grand Canyon, including the Havasupai, Hopi, Hualapai, Southern Paiute, Yavapai-Apache, and Zuni (fig. 4). Important geographical landmarks included the Grand Canyon, the San Francisco Peaks, Bill Williams Mountain, and Red Butte. The Havasupai Tribe roamed the rim of the Grand Canyon and the Colorado Plateau in the winter and spent summers farming in the bottom of the Grand Canyon (Hirst, 2006). When the U.S. Government seized most of their aboriginal territory by executive order in 1882, the Havasupai were locked into 519 acres within the Havasu Canyon along Cataract Creek (fig. 5; Grand Canyon National Park, 2021); their village, known as Supai, is only accessible by foot, horse, or helicopter. In 2022, the Havasupai successfully petitioned the name change of Indian Gardens to Ha’a Gyoh (Havasupai Gardens), honoring their ancestors and reclaiming their historical connection to the Grand Canyon (National Park Service, 2022; Fonseca, 2023).

Havasupai oral histories and belief systems illustrate that every living plant and animal has a role on this earth and a specific spirit that should be protected. “This reciprocity with nature has been described as integral to survival—not only for the ecosystem but humans themselves” (Wall Kimmerer, 2013).

The places of prayer for the Havasupai, Wii'l Gdwiisa, "Clenched Fist Mountain", is known to the Havasupai as the abdomen of Mother Earth. Mat Taav Tiivjunmdva, a meadow, is her navel. The Tribe has long fought to regain some control over these places and to protect them from overuse and mineral extraction.

When settlers moved in and recognized the riches of the region, the Havasupai were pushed into just 518 acres in 1882. The Havasupai grew crops and inhabited more than 1.6 million acres in and around what is now Grand Canyon National Park, including Red Butte and Mat Taav Tiivjunmdva.

The Havasupai, as well as 12 other tribes with cultural and historic ties to the Canyon, suffered further in 1919. As the rest of the nation hailed the decision to establish Grand Canyon National Park, the Havasupai mourned as they were evicted from the lands they had lived, loved and prayed on for millennia. Later on, the remainder of their lands were swept into national forests and other public lands. Some lands were sold to private buyers.

The Havasupai eventually regained another 185,000 acres, yet they were mainly barred from stewarding public lands, both within the National Park and the Kaibab National Forest. Their sacred lands were open to anybody- mineral hunters, recreationists- and several mineral claims were established. While the Kolb brothers were allowed to live in their home on the edge of the South Rim, Havasupai people were barely tolerated.

Ceremonial gatherings were common at Red Butte until the 1980s, when the U.S. Government asserted that the Havasupai had no traditional or cultural connection to the area (Winters, 2016).

The situation has improved in recent years as the National Park Service began engaging with the tribes who call the Canyon part of their homeland and religions to rectify this troubled past.

In 2010, the U.S. Forest Service designated Red Butte and the surrounding area as a Traditional Cultural Property through the National Historic Preservation Act (Mike Lyndon, National Park Service, written commun., November 28, 2023; Winters 2016). However, this sacred area remains under the ownership of the U.S. Government as part of Kaibab National Forest and was designated as part of the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni– Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument in August 2023 (White House, 2023).

Quotes from Havasupai members describing use of Red Butte and other sacred areas to the Tribe and Connections with the Water

“We have found the only way we can protect a thing that we do not want disturbed is by being very, very silent. Not speaking about that painting, that rock, what is behind that rock, because we know what is going to happen to these things if we talk about them. They are going to be destroyed.” —Rex Tilousi, elder and former Chairman of the Havasupai

“People complain that we have no documentation of being in the [area] and say such things like ‘we have never seen them here.’ But animals and plants are still a very profound part of the survival of the Havasupai people, and we have been constantly utilizing these lands over generations.” —Uqualla, a Havasupai Medicine Man and Spiritual Traditionalist

“The Havasupai note that the people’s existence and belief systems are at risk of serious effects that cannot be mitigated if the water becomes contaminated from uranium mining (Tilousi, 2019). Havasupai Vice-Chairman Edmond Tilousi noted, “If the R-Aquifer becomes contaminated, and we must abandon our ancestral home of Supai Village, we will leave the blue-green waters of Havasu Creek behind and consequently will cease to be the Havasuw baja. While we may still breathe air, we, the People of the Blue Green Water, will have become extinct.” (Tilousi, 2022, p. 15).

Concerns about potential effects to water from uranium mining was a driving factor of the mining withdrawal by U.S. Department of the Interior in 2012. The Pinyon Plain Mine is above a primary aquifer, the Redwall-Muav aquifer or R-aquifer, on the Colorado Plateau (Pool and others, 2011). A perched aquifer at the Pinyon Plain Mine site was encountered during the sinking of the mine shaft around 2016 (Energy Fuels, Inc., 2016, 2017); large volumes of water from the perched aquifer have continued to drain into the mine shaft (Energy Fuels, Inc., 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022).

The act of puncturing the aquifer itself contaminates the air and the water according to the Havasupai belief systems (U.S. Congress, 2017) even though uranium ore has yet to be produced at the Pinyon Plain Mine, as of December 2023. Furthermore, water loss mitigation plans are not in place.

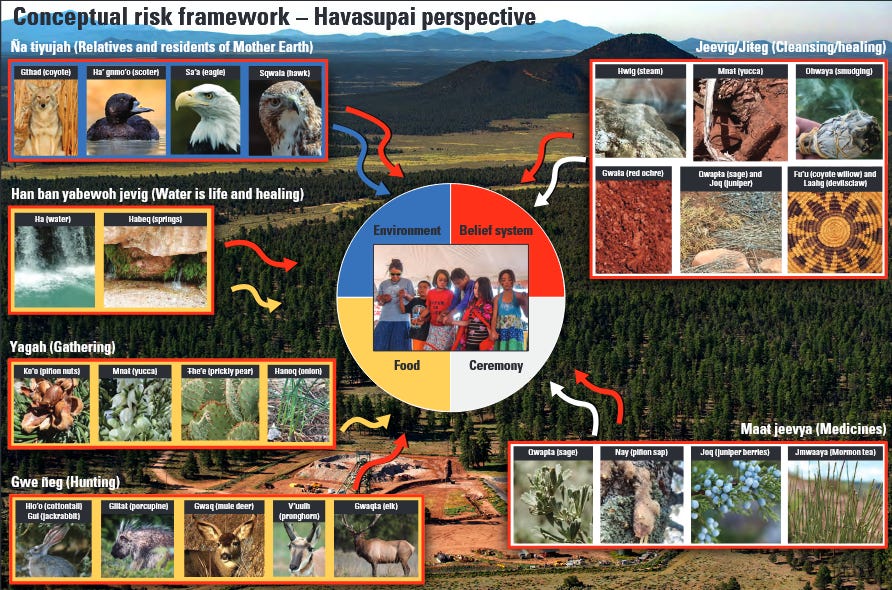

Traditional ecological risk analysis considers various components of the environment (for example, Hinck and others, 2014; Park and others, 2020). Likewise, components of the environment, including all the plants and animals, are important to the Havasupai. The people’s communion with these plants and animals reflects the traditional uses of the Havasupai, and such uses can introduce unique exposure pathways not considered in the original conceptual risk framework (Hinck and others, 2014).

“We have a belief system that they don’t understand,” says the Havasupai elder Carletta Tilousi. “In our stories, where the mine is located is Mother Earth’s lungs. So when they dug the mine shaft, they punctured her lungs.” (McGiveny, 2022)

Conceptual Risk Framework for Uranium Mining—An Update to Include Havasupai Resources at Risk

Conceptual risk models are a working hypothesis of how contaminants at a site may affect the surrounding ecosystem. Historically, model components include sources of contaminants, routes of exposure, and endpoint receptors (Suter, 1996). Conceptual risk models for mining sites are typically conducted from a western science perspective, focusing on human health (for example, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2006, 2014) or ecological risk (for example, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1992, 2003; fig. 10).

Western science has been defined as a knowledge system that relies on application of the scientific method to phenomena in the world in which a proven hypothesis can become theory or truth (Mazzocchi, 2006). However, these risk models lack the Tribal or indigenous knowledge as seen by recent research opportunities from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to expand inclusion of indigenous perspectives into environmental health research (for example, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2023a, 2023b). This deviation from equitable co-existence between humans and nonhuman beings is inconsistent with foundational understanding of many indigenous cultures (Tribal Adaptation Menu Team, 2019). Models that include indigenous knowledge are being developed by groups such as the National Tribal Toxics Council (2015) and the Pueblo de San Ildefonso (2023).

“The updated framework has allowed USGS to take first steps in understanding important resources to the Havasupai, building relationships to improve co-production in our research, and potentially addressing additional concerns outlined in the original withdrawal record of decision (appendix 1).”

The belief systems component is connected to all the resources (in figure 13) because they are important to the Havasupai ways of knowing and being and cannot be separated out—or left out—when considering the risks of uranium mining at the Pinyon Plain Mine.

“Building on interconnectedness, the Havasupai belief systems teach that change or loss happens once Mother Earth is disturbed; change or loss does not wait until a mine goes into official ore production.”

Connections with land, water, animals and ceremony represents healing and cleansing aspects of culture

Important animals (for example, coyotes, bighorn sheep, bald eagle) and plants (for example, piñons, peaches, corn) tie the seal to the land. Richard Watahomigie, a descendant of the first Havasupai elder noted,

“The bighorn sheep are sacred to the Havasupai. When we pass away, we reincarnate into the bighorn and travel along the rim of the Grand Canyon, back and forth, guarding it. That’s why the ram dancers call themselves the Guardians of the Grand Canyon. (Bleir, 2018).”

The Havasupai view the presence of rainbows during their ceremonies as reassurance that their dances and prayers at Red Butte are honored.

The Havasupai have revitalized the ram dancers (fig. 2.2A) after the passing of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 (42 U.S.C. 1996), which protects the rights of Native Americans to practice their traditional religions by ensuring access to sites, the freedom to worship through ceremonials and traditional rites, and the possession and use of sacred objects.

The Guardians of the Grand Canyon and Politics

Because the Havasupai once lived and farmed 1.6 million acres, there are burial sites, sweat lodges and archeological rock writings in the Grand Canyon, Kaibab and Red Butte areas.

The Havasupai Tribe provide testimony at the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources to protect the Grand Canyon.

Chairwoman Jones wrote an opinion piece in the Arizona Republic to protect against harm for the Havasupai and other Nations in the area.

Newsweek published an op-ed written by Chairwoman Kissoon about the damage of uranium mining.

The uranium mining debate and politics are complex.

The EPA recently agreed to cleanup of seven abandoned uranium mine sites on the Navajo Nation.

Films like Oppenheimer and Downwind show the horrors of humanity- power, greed, control, wars and nuclear testing. Let’s learn from the past. Hubris harms. Engage in peace. Let’s humbly honor humus not hubris.

Engage in your community and in your world.

In previous essays, Wildlands shared stories about my work leading several initiatives for conservation-protection-restoration, and other issues effecting All of life. One such time was to deliver signatures to protect wildlife and habitats. We met with State leaders in Arizona and urged them to revise the Mining Law of 1872. During our meeting, our group was told that Senator Harry Reid had mining interests and that he held up updating mining laws. We then discussed the importance of our tax payer dollars, no taxation without representation, the legalities of conflicts of interest with politicians and the corporate-military complex. Our Founding Fathers envisioned a small government that protects life and property. Your voice is needed— I encourage you to meet with your local Representatives. Never under estimate the power of One- I have spoken for wildlife, ecosystems, and trees at State Capitols, Councils, County Boards and State Agencies. Let’s return to small governments and our personal Sovereignty.

It is an honor to speak for common sense legislation that protects and conserves All of life. Please join me!

Support Wildlands mission: Regeneration Nation to restore soils and souls, shift paradigms, increase and celebrate interconnections to reduce harm. Freedom is justice for All.

Reciprocity is exchange- our way of compensating for all that flora and fauna give us. Giving back expands nature and more than humans gratitude for us. Generosity of our hearts, minds and hands (actions, thoughts, words and deeds) give us compassionate, empathetic purpose- Restoring Soils and Souls is sustainable conservation. We are all a part of the biota. What we do to one, we do to ourselves.

My great grandfather was a farmer and friends with a U.S. President. My great aunt babysat the President’s daughter. Another ancestor fought in the American Revolution. My partner, a Physicist who is a Citizen of the Cherokee Nation and I now own farmland- land that his family has owned since 1902. Food, farming and freedom are infused in my life and restoration-conservation are a part of my Soul.

“A Poet with a Purpose” as a Wild and Free Nature Nomad, is growing organically- through art, poetry, essays on Wildlands and through Sustainable Tucson Habitat Restoration projects.

Introspection and Action Steps for You: Share your thoughts:

Would including an All of life perspective help us be healthy, well, peaceful and prosperous?

How can we implement the All perspective in our daily lives?

Are you willing to be the change and teach others how to live in truly United Nations?

Realize the hypocrisies in your life and unite your inner conflicts for peace and prosperity. Awareness changes the world One person at a time. Be YOUnited within and Unite with others for a better world.

Take the Poll:

Ask your friends to take the poll. Results will be shared with USGS, the Havasupai, EPA and U.S. Forest Service.

Please let the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Environmental Justice and the U.S. Forest Service know whether you support or oppose Canyon Mine (renamed Pinyon Plain Mine) near the Grand Canyon.

Greed and hypocrisy are the dis-ease that is killing our planet. Get your medicine in Wildlands and Be the Cure. You make a difference with compassion and empathy for peace and prosperity. Heal inner conflicts and change the world.

Let’s humbly honor humus not hubris. Please help the mission of Wildlands regeneration nation- together we restore soils and souls! Thank you and All Blessings to you, my friends!

Your voice matters! Take the poll: "Do you think uranium mining should be banned in the Grand Canyon Watershed?"

and,

Sharing a note from a Subscriber: "I just wanted to let you know that I absolutely love your content! It's always so engaging and fun. Keep up the fantastic work!" -RF

The Havasupai Tribe, Hopi Tribe, Hualapai Tribe, Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, Las Vegas Tribe of Paiutes, Moapa Band of Paiute Indians, Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, Shivwits Band of Paiutes, Navajo Nation, San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe, Yavapai-Apache Nation, Zuni Tribe, and the Colorado River Indian Tribes all maintain strong historical, cultural, and spiritual connections to the Grand Canyon region